The Essex Coupe

/The following story comes to us from Alan London, who's father worked at the Essex Aero Ltd., builders of a very unique Allard Special. After that is a brief story about the Essex Coupe from an old AOC newsletter and finally a note from a previous owner.

One Jag or Two?

That’s a question I’ve recently posed, in person and by email, to folks on both sides of the Atlantic. Perhaps surprisingly, especially to us Jag-nuts, the responses have leaned predominantly toward the side of: ‘TWO’!

True, the two cars do indeed share the sleek, classical lines indicative of the early nineteen-fifties, but there, the similarities end. Behind the question lies a story, in the main untold – so without further ado, let’s travel back through several decades, to the mid nineteen-thirties.

Essex Aero Ltd, was founded by Reginald (Jack) Cross, with the assistance of my father Lionel (Jack) London.

In 1937 their firm, which in the early years specialized in the manufacture/repair/modification of aircraft components, relocated from Marylands Aerodrome, Romford, Essex (hence the company’s name) to the Gravesend Airport in Kent, when the Percival Aircraft company vacated the premises.

In their new location, Essex Aero was responsible for servicing local, private aircraft, plus those operated by the airport-based Flying Training School. In addition, it began experimenting with Magnesium Alloy and utilized the metal in some of their products. The opening in 1938 of the Royal Air Force Elementary Reserve Flying Training School provided the company with additional maintenance assignments.

With World War Two looming, the airport was sequestered in 1939 by the Air Ministry, and designated a satellite station of RAF Biggin Hill, which had been assigned the task of defending London and the South East. Gravesend’s proximity to the English Channel made the airfield an ideal candidate for Biggin Hill support.

During the Battle of Britain period, the airport was home to squadrons of Blenheims, Spitfires, and Hurricanes, which were serviced by Essex Aero, and repaired as necessary, on mission return.

Throughout the years of conflict, my father’s company, in tandem with its war-service, continued to hone its knowledge of Magnesium Alloy. So much so that on conclusion of the war, when the Allied countries created a ‘team’ to compile not only the ‘lessons learned’, but to also examine German technological advancements. Essex Aero were asked to represent the Magnesium Alloy community at the team’s subsequent conferences/conventions. The company had swiftly established a reputation as a world-wide leader in M.A. technology, with its representatives frequently being invited to deliver lectures on the subject.

Although still contracted to the Air Ministry, the post-war years saw Essex Aero rapidly expand its workforce and its range of business, moving into the commercial world. It began producing a variety of M.A. items such as lightweight hospital beds, fold-up chairs, and soft drink, beer, and milk crates.

Their star truly shone, as was evidenced by the giant Essex Aero four-point star, fabricated solely from Magnesium Alloy. Captured in the beams of three powerful spotlights, the star was suspended over London’s Northumberland Street, and became a focal point of the 1951 Festival of Britain celebrations.

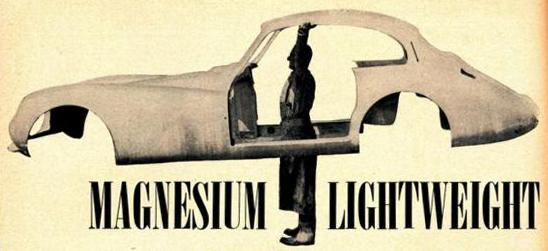

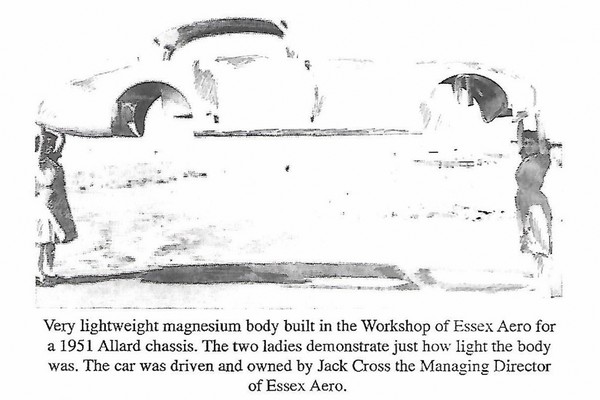

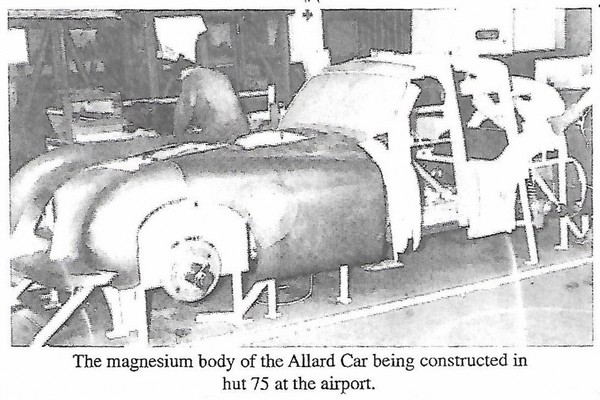

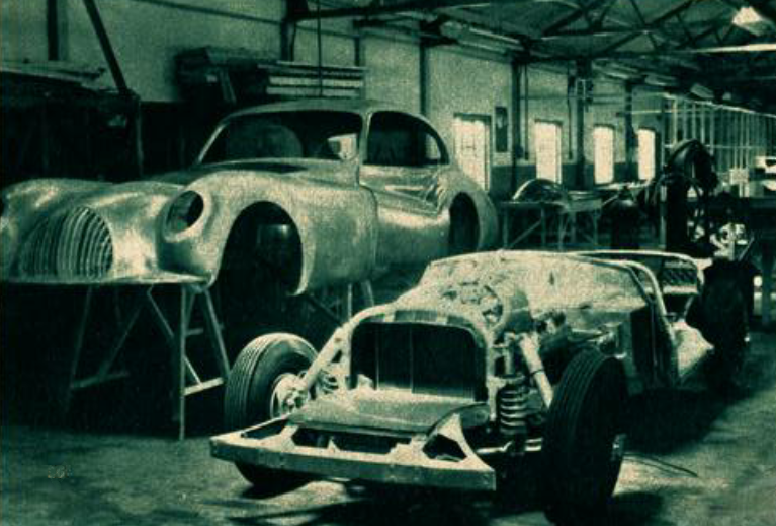

In 1952 Essex Aero designed and manufactured an all Magnesium Alloy-bodied Allard sports coupe. The body panels, each hand-formed, were welded together into a single-piece configuration. A standard Allard J2X chassis was lengthened to accommodate the sleek body; a shell so light, that, at a weight of around 140-pounds, it could be held aloft (at the point of center-of-gravity) in its entirety by a single man, and also, from each end, by two ladies – as is shown below in the photographs that were extracted from the Essex Aero archives.

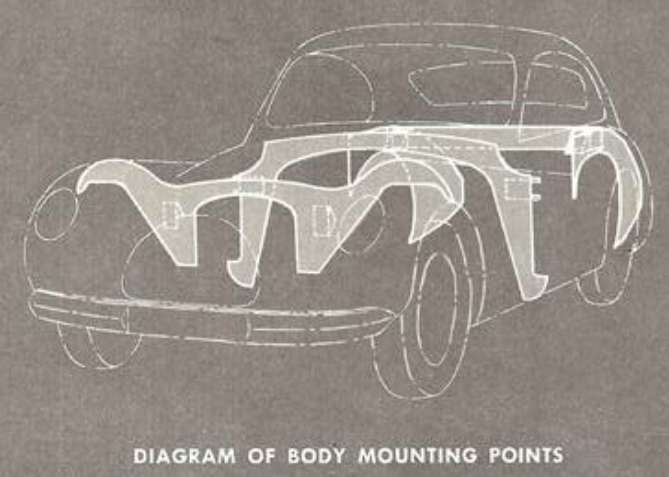

Attached by a mere six silent-block rubber mounting points, the body could be swiftly removed as one-piece, thereby exposing and providing access to the principal mechanical components for any necessary maintenance or repairs.

‘Dad’s Allard’ was powered by a 3,917 cc. Mercury V8 engine with a compression ratio of 8.1. Top speed was a reported 135 mph. The car featured a four-speed electric, pre-selector Cotal (French) gearbox, and thus no clutch was necessary. In line with company traditions, this beautiful, stylish machine was unflatteringly named: ‘MAGBODY’!

My father’s friend and senior partner, Managing Director Jack Cross, whom both mum and dad would affectionately refer to as ‘the old man’, was the driver behind the project. Both he and my father shared a passionate belief that magnesium alloy would, given time, prove to be a far superior material than the fast-approaching soon-to-be rival, gaggle of plastics! Jack Cross was also the driver (and proud owner) behind the wheel of this truly unique vehicle which, incidentally, Sydney Allard, the founder of Allard Motor Cars, had taken an interest in, keenly following its progress from conception to completion. Jack could be frequently spotted buzzing around Kent’s narrow country lanes in his... new ‘baby’!

Sadly, in early 1956, Martin’s Bank (later Barclays’s) placed Essex Aero into Receivership. All assets were swiftly disposed of, including the one-of-kind Allard, which was literally stolen for a mere 350 British pounds!!! Our family, with much-depleted belongings in tow, relocated, and alas, subsequent communications between Jack and Jack were reduced to mere telephone conversations.

And so the car just kind of fell off the London’s landscape. But despite all, my father, who lived to just shy of one-hundred, never let up on his life-long love affair with that Allard, and also never ceased, most-like because of his son’s Jag-affections, to prod and insist that ‘the car that the two Jacks built’, in both of their minds, was designed and produced well afore Jag’s XK 140!

Just recently, my wife Maureen, herself an owner-member of our Jag Club, whilst rummaging through some of my parent’s belongings, came across the original photos of the Allard. It was her idea that we, in memory of dad, and because the car represented such a proud episode in his life, leaf back through time’s pages, and endeavor to trace the route she had traveled from the 1956 sale to the present day, trusting to fate of course, that MAGBODY actually did indeed still exist!

Fortune smiled – but feebly; for many any a gap still exists in her history, and no pot of gold was to be found at her rainbow’s end! We did discover that around twenty years ago, the car received a new Allard P-Type body, and the revolutionary Mag-Alloy body-shell... the prime objective behind our search, once removed, had been discarded – but, we questioned, to what end? [Ed: The Magbody was placed onto a P chassis...see Thurston note below]

By chance, our continuing probe brought us into contact with Colin Warnes of the Allard Register. With his help, we were able to locate the MAGBODY’ shell. It is currently housed at Heritage Classics, a Middlesbrough (Teesside) car restoration company that, coincidentally, specializes in Jaguar renovations.

I mentioned earlier that fortune had smiled, but…!

I was able to make contact with John Collins, the founder and owner of Heritage Classics, and a super gentleman to boot. Understanding and appreciating the motives of our project, he immediately supplied me with a series of photographs, a few of which are shown, plus an update: As I’m sure you will understand, his information generated within Maureen, Colin, and myself, a rash of very mixed feelings.

Sadness and a sense of dismay: that such an example of artistic expression and a long-obsolete skill, has been reduced to, by all appearances, a barely clinging-together collection of metallic leaf flakes. The buffet of one mighty wind gust, one fears, would scatter all in a thousand different directions!

A muted joy: that what once was, still is – though barely!

As John explained, the owner prior to the current, operated a trailer-manufacturing company in Aberdeen. Requiring additional space for his business operations, MAGBODY was moved into a field, where it remained for fifteen years.

As John warned me, and is oh so plainly evident, the Mag Alloy material has deteriorated far beyond any possible repair. He has therefore been tasked by the current owner to replicate all of the panels in aluminum. As you can see, the task has already commenced, but at the time of my writing is in temporary abeyance. John has promised to keep me updated as the project again moves along.

In our correspondence, I provided John with background material on Essex Aero and my father’s deep involvement in MAGBODY’s origins, (as discussed in this piece), and he intends forwarding it on to the current owner. Eventually, and with hope, between the three of us, it may be possible to color in some of those afore-mentioned historical gaps.

For Maureen and I, there remain pages still to turn before the book on MAGBODY can be closed, but I hope that for fellow Jag-fans, the story so far is an interesting one.

For us ardent enthusiasts, an emphatic “ONE” is the obvious answer to the question I initially posed. But, just for a moment, blank off the signature Allard grill and…maybe, just maybe, albeit tongue in cheek, my old dad had a point…you be the judge!

-Alan London

A NOTE ON THE ESSEX AERO from the October 1965 AOC Newsletter

This 2 plus 2 coupe was built on an extended Allard J2X chassis by Essex Aero Ltd, of Gravesend Airport in Kent, for R.J. Cross, managing director of the company, in l952. During the war years the firm made fuel tanks and other parts for de Havilland Mosquitos.

Like the standard J2X the Aero's chassis, 2224, had a divided front axle with forward radius rods, deDion rear axle, coil springs, hydraulic dampers, 12-inch Lockheed brakes with Alfin drums and air scoops, and 16-inch wire wheels.

Claimed to be the first car body built entirely of magnesium alloy (DTD 118A) the 16-gauge panels, 12-gauge pillars and supports achieved a remarkable saving in weight. The bare shell, without front seats and floor, but with doors, grille and luggage locker floor weighed only 140 lbs. Taken at the point of balance, a foot or so back from the screen pillars, the body could be held aloft by one man. The 20-gallon petrol tank weighed 15 ½ lbs., compared with 39 ½ lbs. in steel, and the front bumper was a mere 8 1bs. Torsion boxes ran beneath the door openings and argon arc welding was used throughout.

Location on the chassis was by six high tensile steel bolts in Silentbloc rubber units which, in conjunction with plug-in electrical connections, allowed the body to be lifted off for any extended servicing to the running gear. A large bonnet gave access to the engine and radiator. The instrument panel, controls and front seats remained with the chassis when the body was lifted and so it was possible to test drive in stripped form. Even with full trim, spare wheel, radio and Clayton heater, the Aero was 6 lbs. lighter than the standard J2X with Chrysler engine.

The black and grey Aero was first driven by a 3.9-litre Mercury V8 fitted with Ardun ohv heads. The gearbox was a four-speed electric Cotal. Mr. A E Freezer who had the car painted red, experienced some trouble with the Cotal, and later came a Chevrolet V8 and GMC automatic transmission.

A Note From A Previous Owner, Gerry Auger…

Hello and Happy New Year Colin, hope the following is of interest. I purchased the car in the early 1970s from Mr. Laurie Ferrari, he owned a few cars at various time and was known to other AOC members. The body color was a mustard yellow and the car was running with a small block Chevy and automatic. I believe it originally had a Ford Pilot engine with a Cotal preselect gearbox. I remember a photo of the car at Brands Hatch in the`60s when it was painted bright red. I ran the car for a while then fitted a 365in3 Chrysler Firepower hemi linked to a 4-speed manual from an Alvis speed 25. The hemi tended to overheat in traffic even with a refurbed radiator and twin electric fans. In spite of that I did compete at Goodwood sprint meetings, a club race at Silverstone and the Valence Hill climb (twice) all without success. The hemi was powerful but VERY heavy and I soon learnt NOT to lift off in a corner as the car would swop ends!

I eventually removed the (very light) magnesium body stripped it and resprayed it in a Ford color, "diamond white", the chassis was stripped and painted silver and the interior was reupholstered with a cream-colored leather which had red piping. I refurbished the wooden dash and had the instruments overhauled as were the brakes which had Alfin drums with steel liners.

I then fitted a 331in3 Caddy, but a change of personal and financial circumstances meant that I was unable to continue running the car and after storing it for a few years I sold it to friend and club member John Peskett who removed the body and shortened the chassis to that of a standard J2X.

A note from current Chassis Owner, Jerry Thurston:

Factory records show a Cadillac unit being fitted after the Ardun head Ford (that was I think a 390 engine)

The Chassis did not receive a P type body when the Magbody was removed. Rather, the Magbody was put onto a P-type chassis, the idea being that rather than the body being discarded it would be preserved, sadly 14 years in a Scottish field put pay to it as you can see from the pictures! It's a pity that the shell had gone too far to be repaired and had to replicated be in Aluminium Alloy, obviously it was the sensible option though. However on a positive note it's wonderful that while the original body has 'gone' at least the design will survive

When the Magbody came off and the J2X chassis was revealed it was found that most of the standard under structure was still there, for instance the standard rear body hoop had merely been notched and laid back. This meant that it was easy to bring the chassis back to standard configuration base. Essentially by sorting the body hoops and reversing the lengthening process (merely cutting it on the additional welds and removing the extra box sections that had been added to lengthen it). The chassis was then given a 'standard' J2X body to bring it back to the configuration it would have been in had the chassis not been assigned to special purposes and continued through the build in the Allard Works .

PKJ 412 although now a 'standard' J2X, the car pays homage its history by carrying a Essex Aero Ltd. logo on her side.