The P1 Road Test

/I’ve always had a soft spot in my heart for the Allard P1. Let’s be honest, it’s not the prettiest car in the world. However, when you compare it with the competition at the time, I think it was actually pretty attractive from a “form follows function” perspective. The competition featured a lot of chrome and sweeping curves that made them look more glamourous than they really were. Engine-wise, all of the P1’s compatriots at the time we powered by straight 6 engines (or less), while the P1 and Ford Pilot were powered by war surplus Flathead V8’s.

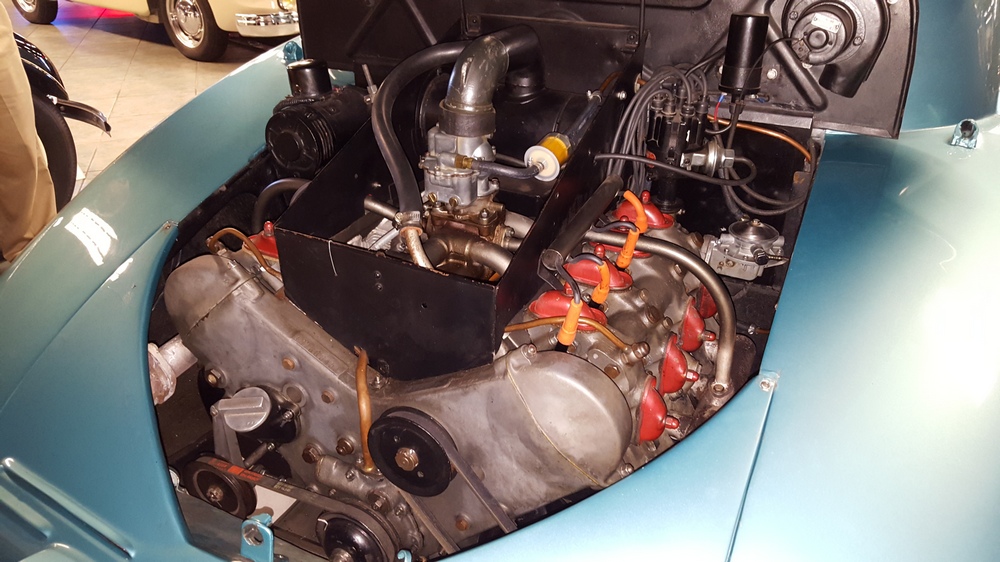

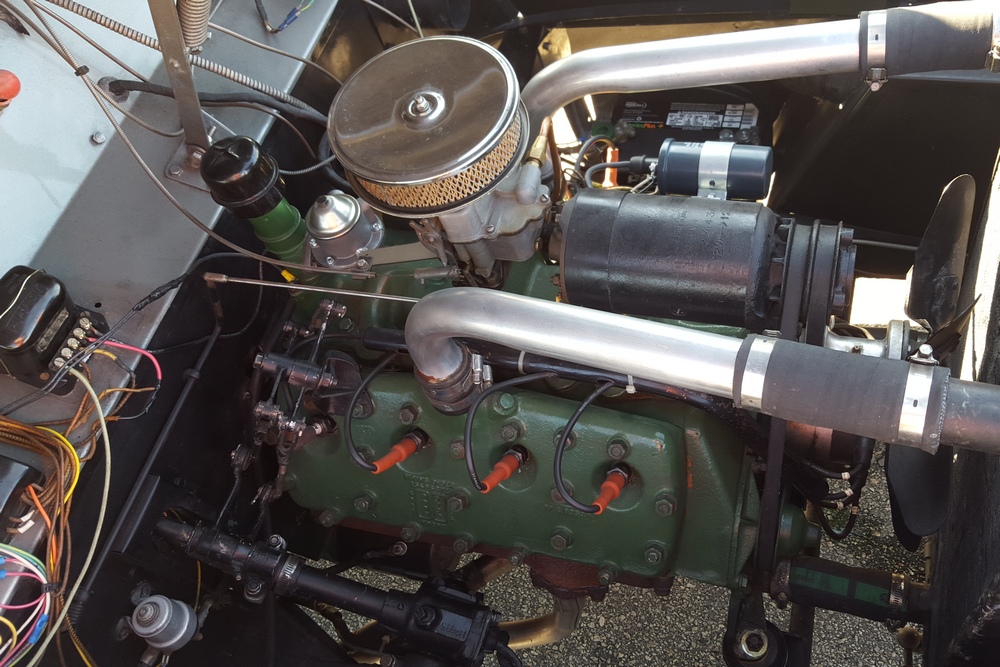

We’re all familiar with Sydney Allard’s 1st place finish in the 1952 Monte Carlo Rally. But the Guv’nors P1 was by no means a standard P1…it was more of a P1X, featuring coil sprung front suspension and a DeDion rear suspension. The flathead powering the car was also the more powerful Mercury 24-stud flathead with Allard dual carb manifold and aluminum heads*…plus a few other tricks that we don’t know about. When you think about it, the P1 was really one of the first muscle cars – in stock trim it was relatively anemic, but with a few of the option boxes selected, you could blow the doors off of just about any other tin-top on the road.

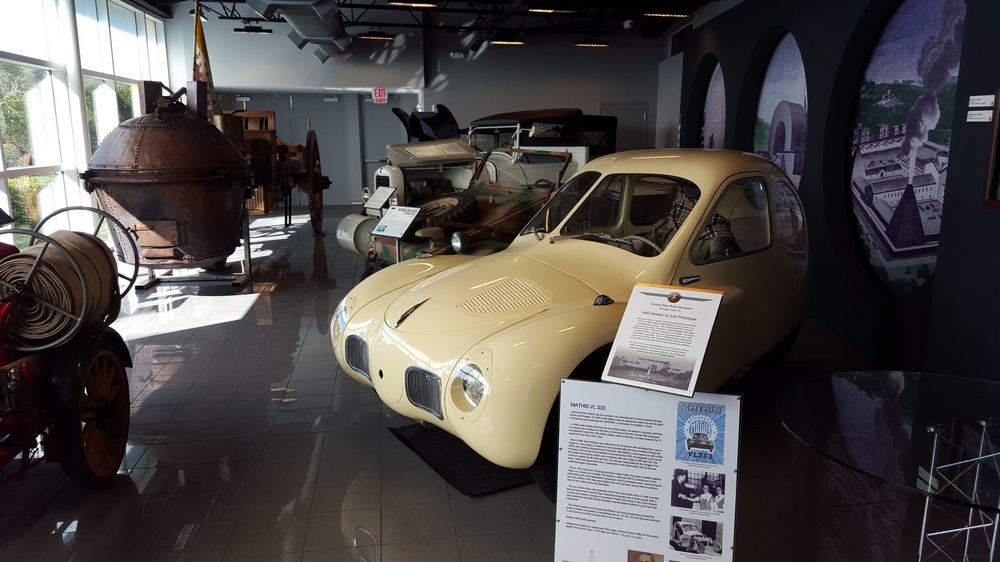

Unfortunately very few P1’s remain today, we know of a little over 40 cars out of the 559 cars that were built – and a handful of those 40 or so cars have been converted to J2 replicas. Even rarer is finding a running P1 here in the USA, we know of only 3 or 4. Fortunately one of those cars resides at the Tampa Bay Automobile Museum. The TBAM owns chassis #1885, which was originally sold through Bristol Street Motors on January 13, 1950. It was painted grey with a marron interior. The car was imported to the United States in 1958. The Emmanuel Cerf was kind enough to take me for a spin in the car and he even offered me the keys!

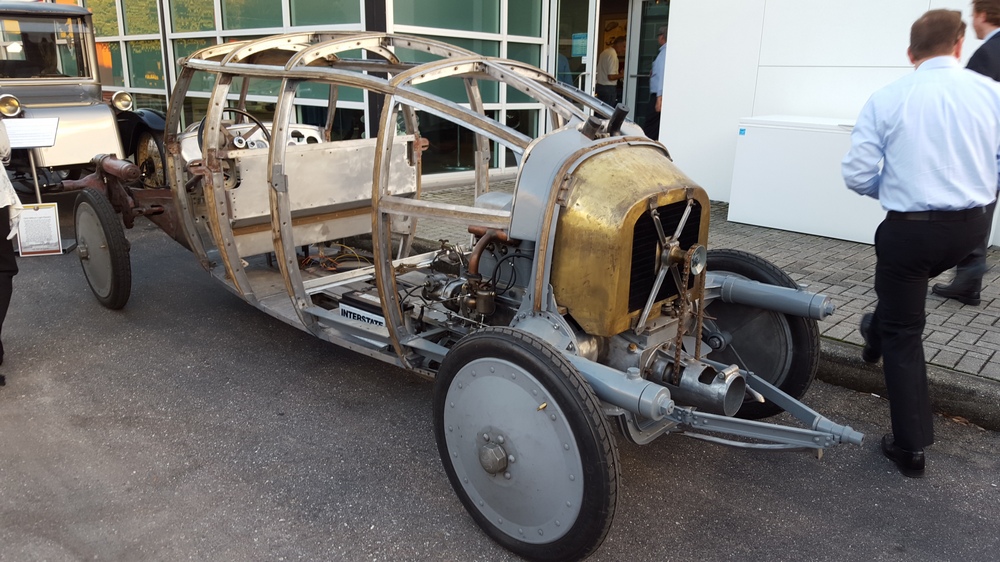

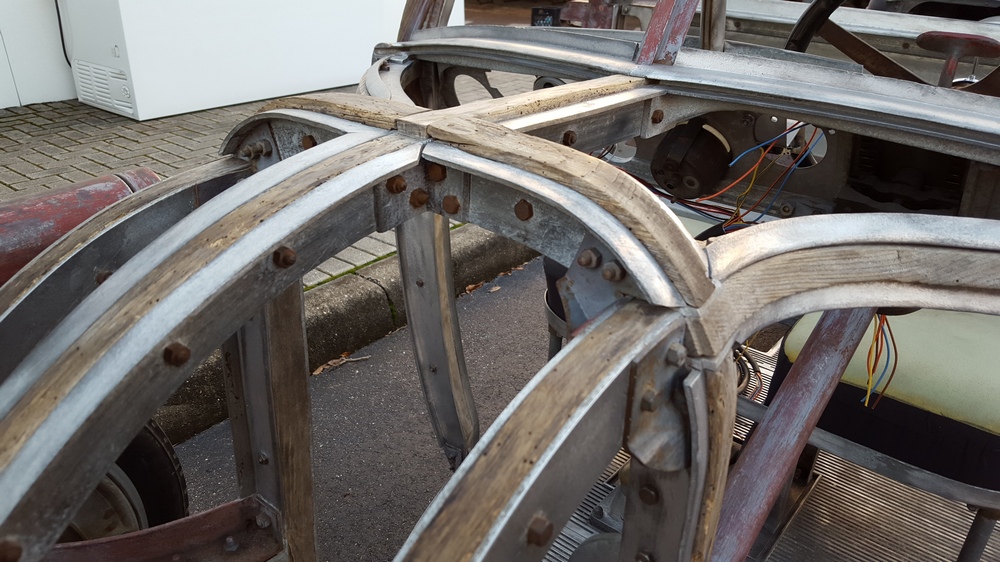

1885 is in very good mechanical and cosmetic condition. It has been lightly restored and maintains what appears to be the original factory build quality. The doors close with a solid clunk, but there is a fair amount of flex. The seats are comfortable and I must say the suicide door entry is a pleasure – it’s a shame the design is frowned upon today.

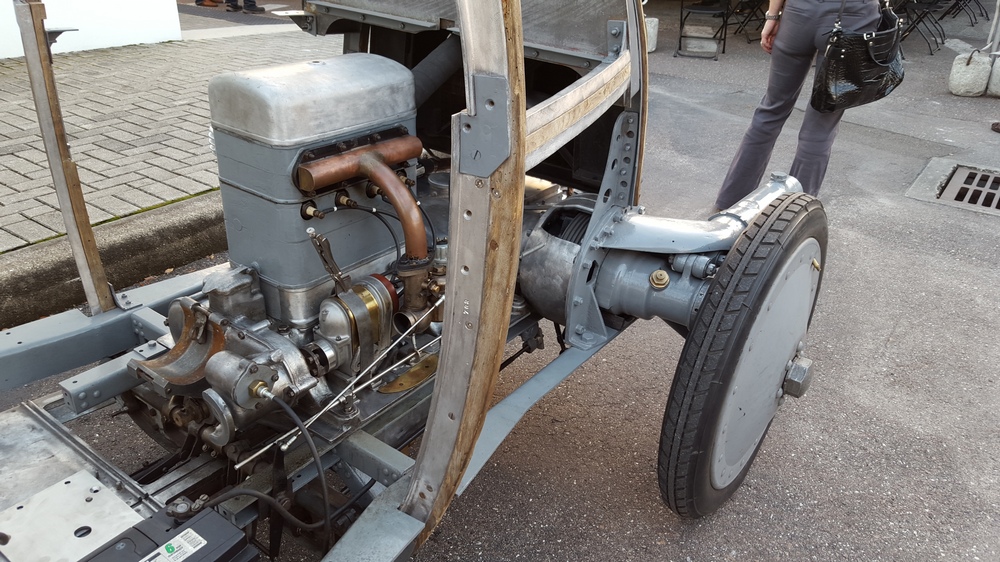

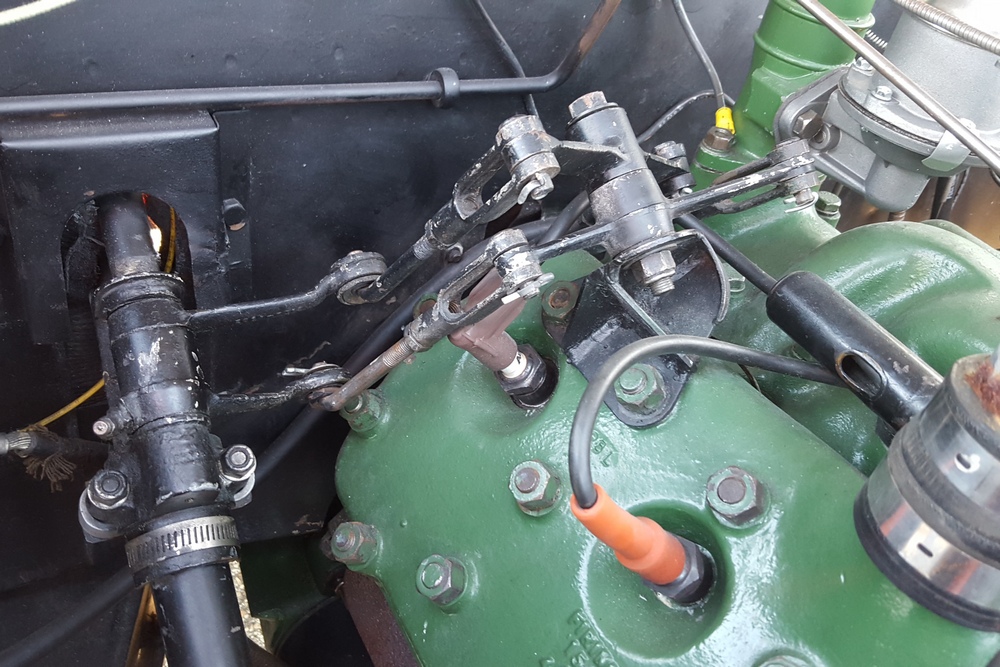

Driving the car was a bit of a mixed bag. Acceleration is quite good, especially when keeping in mind that this was a British passenger car from the late 40’s. The steering was heavy and the car wallowed a bit, but it was smooth at speed. My biggest frustration though was with the 3-speed column shifter. The shift linkage is quite complex, consisting of what can best described as a couple of scissor linkages that miraculously shift gears with a deft movement of the shift lever. I struggled with finding first gear from neutral – at one point the linkage jammed completely at an intersection. Fortunately the Cerf’s mechanic came to our rescue and was able to fix it after a few minutes. Apparently the scissor linkage can lock up on itself when handled incorrectly by a ham-fisted American like myself.

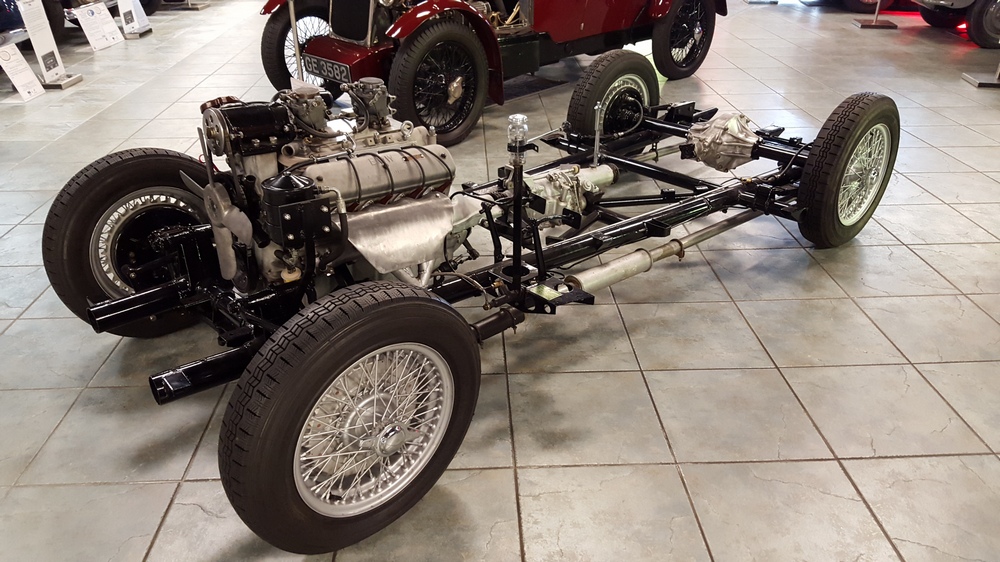

Other than that, the car was fun to drive. By no means does it handle like a ’56 Chevy Bel Air, but they are two completely different cars. A Chevy or Ford from the mid 50’s had the benefit of being created by hundreds of engineers and designers; and put together on a production-based assembly line. The J1, K1/2, L, M, and P1 cars essentially shared the same chassis layout with the only variations coming in wheelbase and a later switch to coil springs. Allard had just a few draftsmen & engineers; the cars were styled by Sydney and friend Godfry Imhoff! Even comparing Allard with its contemporaries of Austin, Alvis, Jaguar, and Triumph – what Allard accomplished with the P1 and the other cars was pretty amazing.

When driving the P1, I could imagine the car with 50% more horsepower, tuned suspension, and fresh tires blasting through the Alps like Sydney Allard. Sadly the shifter quickly brought me back to reality. However, with some more seat time I’m sure that I could come to grips with that blasted shifter. If I ever bought a P1, I would give serious consideration to converting it over to a floor mounted shifter. Sacriledge! I know, but in the name of drivability, it should be considered.

While the standard flathead was fairly anemic, it was easily tuned. In America, there was a wide variety of tuning parts available to the intrepid hot rodder. Unfortunately American tuning parts were nearly impossible to obtain in post war Europe – while exporting was essential to rebuilding post-war economies, importing foreign car parts wasn’t exactly at the top of the governments priority list.

-Colin Warnes

*The Allard dual carb manifold is a direct knock-off of Eddie Meyer’s manifold – it was replicated without Eddie’s permission. The Allard aluminum manifold was a direct copy of Edelbrock’s flathead manifold, which was apparently done with Edelbrock’s blessing. The parts were acquired by Reg Canham on a trip to the US in 1948 and smuggled back to Britain as carry-on baggage aboard his Trans-Atlantic flight.